Fermentation may seem like a mysterious intersection of science and magic, and in some ways, it is. The invisible bacteria and yeasts floating around in the air and living on food and surfaces can drastically change the nature of food. These effects can have less-than-appetizing effects, but when guided by a steady hand, the transformational power of fermentation results in some of the most delicious things on the planet: bread, wine, cheese, pickles, beer and so many more.

At Community Cultures, an educational organization based in Pittsburgh, this power is placed into the hands of home cooks. The organization’s schedule of workshops brings fermentation to the people, demystifying and teaching everything, from the basics to more advanced and obscure techniques. Its founder, Trevor Ring, has followed a life-long fascination with, and passion for, food, with his journey bringing him to Western PA and the creation of Community Cultures.

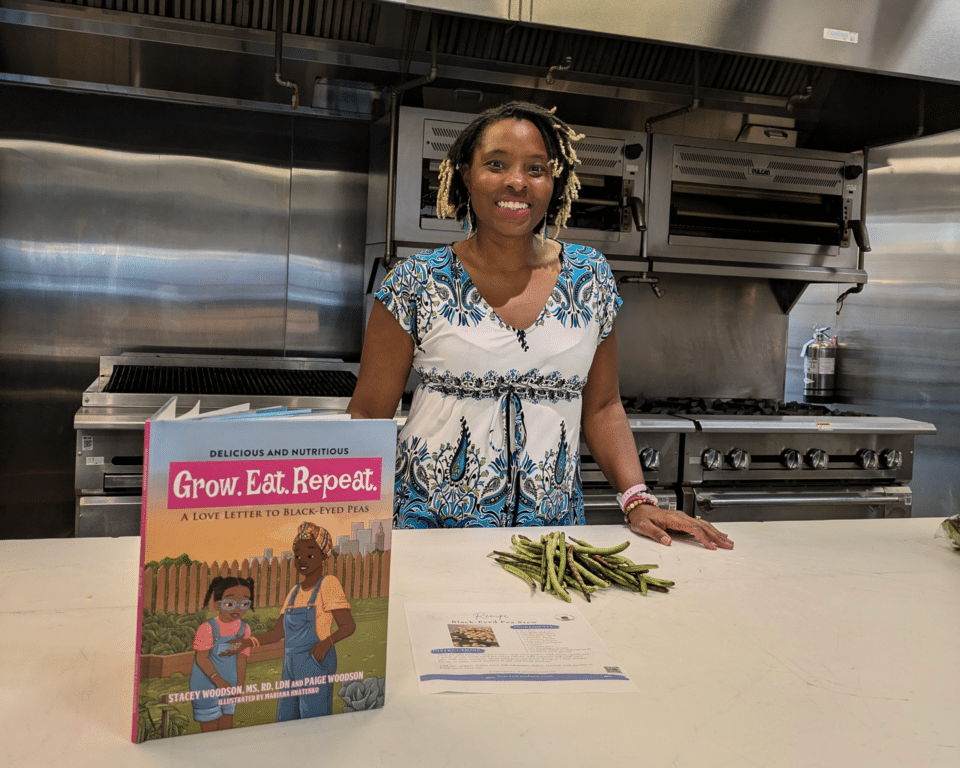

Trevor Ring of Community Cultures

PA Eats: Can you just tell us a bit about yourself? Where are you from? Was fermentation something that was around during your childhood?

Trevor Ring: I grew up in Maryland and currently live in Pittsburgh, PA. I’ve spent most of my adult life in the Northeast, from the Adirondacks and upstate Vermont, to Western Massachusetts and now Pittsburgh. I have some Eastern European roots in my ancestry and heard stories of my great-grandmother making lacto-fermented pickles and sauerkraut once she landed in the US; however, this tradition did not pass down. It seems as though the culture of the industrialized food revolution stripped my family of some of its roots, like many others, in relation to fermented products. Why make sauerkraut when you can buy it canned and save time? My mom also hated eating sauerkraut growing up, so this is probably a significant reason why I did not experience it at home as a child.

Where did your passion for fermentation originate?

I became interested in food in high school. I wasn’t specifically good at cooking, I was just very curious. This led me to pursuing a culinary degree from Paul Smith’s College in the Adirondacks. During that time, I spent a semester abroad in Italy. Through that eye-opening — and somewhat cliche — experience, I learned about how connected many Italians are to food culture, tradition and a sense of identity. This greatly contrasted with my own experience in the United States, even in culinary school. My time in Italy inspired me to pivot my interest in food, from culinary to sustainable agriculture.

After getting an Associate’s degree in Culinary Arts from Paul Smith’s, I ventured off to another college located in the middle of nowhere: Sterling College, based in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont. I quickly became connected to my food source, and slaughtered chickens, butchered pigs and planted many vegetables for the first time in my life. It was here where I was introduced to fermentation. In a value-added products class, I fermented vegetables for the first time. Around the same time, a close friend introduced me to kombucha at our local co-op. The flavor, spontaneous and adventurous food opportunities, and nutrition that I experienced through fermented foods exhilarated me. Within a year, I was using kombucha vinegar to cure my stomach aches, selling my dorm-brewed kombucha (with labels made from post-it notes and scotch tape) at the local farmer’s market, making salami in class and fermenting fun combinations of vegetables with friends. After I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Cross-Cultural Food Studies, a self-designed major, I took my fermentation passion with me wherever I went, constantly experimenting, educating myself, and sharing my products with friends and family. Within a decade of my introduction to fermentation, I had started a fermentation education and products business (first called Tringo Cultures, now called Community Cultures), worked many other value-added fermented product businesses, and studied with [noted fermentation author] Sandor Katz.

How did you transition your fermentation passion into a career?

I should be clear that I’ve never solely relied on fermentation as a main source of income. I hope that day comes soon, but it’s always been supplemental income. All that said, it seems that my entrepreneurial spirit was awakened when I discovered fermentation. Most of my creativity up until that discovery was expressed through music (I play electric bass), and for the first time I felt like I had another realm of creativity that I could explore and share with the world, outside of music. What first started as a tiny overly-fermented kombucha business in college later turned into helping a farm with product development (making kimchi and sauerkraut), teaching workshops, running a fermentation CSA. There were times when I thought teaching wasn’t for me, or that I never wanted to run a business focused on fermented products, but as time has passed, I realize that I love talking about fermentation and sharing it with others. I always knew I would have a career in food, but if you told me I would be launching a career in fermentation 10 years ago, I would be pretty surprised.

When did you found Community Cultures? What drove you to create an educational platform around fermentation?

Community Cultures was founded in 2015. It started off as the name Tringo Cultures, and in 2019 I changed the name to Community Cultures, which felt like the perfect step towards building a community of both microbes and people. Once my stubborn self recognized that fermentation is never about the self, and always about the community (whether or not you’re fermenting alone), I landed on a name that felt like a perfect combination of words that describes the process of fermenting food. It’s a symbiotic process between many different microorganisms and humans, therefore a multi-species community effort.

I never thought I’d be a teacher, and never felt like I had the ability to speak clearly enough to really describe a process to someone and show them how to do it. This changed after I was gifted with a load of new information when I assisted Sandor Katz with a two-week fermentation intensive course at my alma mater (Sterling College in 2014). I had so much information that I had to share with the people around me. In fact, I interrupted a nine-month permaculture internship at an intentional community in Western MA to assist with the fermentation course, under the condition that I would come back to the community and share my knowledge. After teaching workshops to many groups at the intentional community, I realized it was something that really fed my soul. It was one of those experiences where I felt like I could teach a fermentation workshop instead of eating dinner. It was literally satiating in that physical sense, as well as the spiritual. Since that year, I’ve been teaching workshops, on and off, from Western Massachusetts to Pittsburgh.

What are Community Cultures workshops like?

Currently, I do not have my own physical teaching space. Up until recently I’ve almost always taught at other businesses or organizations. With the pandemic, I’ve pivoted to doing a lot of virtual workshops, and in some sense, my teaching space has recently become my own kitchen. I’ve also done many virtual collaborations with other fermentation educators over the past year that I met through the online fermentation community. In October last year, I organized a large fermentation event called Ferment for Food Justice. Inspired by Bakers Against Racism and a fellow fermenter, Julia Skinner of Root Kitchens in Atlanta, the event spanned across two weekends, included more than 70 fermentation presenters from all around the world, and it donated all its proceeds to five different BIPOC-led food justice-oriented organizations. The event was a response to the murder of George Floyd and the protests for racial justice that followed, as well as a way of dispersing a wide array of fermentation knowledge to the world through pay-what-you-can donations. Since that event, I’ve done numerous other smaller virtual events while collaborating with other fermenters. Many of these also donated 50 to 100% of its proceeds to different organizations.

My workshops are composed of different elements: I introduce participants to share about themselves and talk about “what food they are feeling” in that moment (as well as their relationship with fermentation); I provide a broad synopsis of what fermentation is; I explore historical and cultural significance of different products; I dive deep into the specific ferment(s) of the day; I do demos and show-and-tell with products I’ve already made; and I always allow space for questions and conversation.

Talk to us about higher ed and food. What do you think is gained in institutions vs. self or community education?

As someone with so many interests, I always felt a desire for more depth of understanding within the world of food. I also felt the need to ground my ideas and find clarity in what I wanted my future with food to be. My hope was that pursuing an MA in Food Studies from Chatham University would help me explore other dimensions of food that I hadn’t engaged in as much (such as the sociological, political and analytical sense that an academic lens can provide) and allow me to make well-informed decisions about my own future and the broader future of our food system.

My graduate degree has helped me show up as a well-informed educator. While I don’t have the answers to every fermentation question, I believe that my academic background has provided me with a lens that can better navigate bigger conversations and presentations around culturally-relevant foods, food access, cultural appropriation and the myths of fermentation. It also helped me recognize my privilege and the reality of folx from marginalized communities. My goal for many of my workshops is to break down barriers to make the topic more accessible, whether that is using pay-what-you-can pricing (with no one turned away for lack of funds), talking about how to reduce food waste in the kitchen with fermentation, or simply keeping instructions simple while demystifying myths that make fermentation seem scary.

My master’s thesis was actually about offering pay-what-you-can fermentation workshops within a multi-revenue stream, for-profit fermentation business. I found that with the right business model and approach to marketing, I can create a financially sustainable business while relying on pay-what-you-can pricing for my workshops. All this being said, almost all of my understanding of fermentation happened outside of higher ed. I learned from other instructors, reading, and a lot of experimenting at home. Fermenting on your own, or even creating a business around the topic, does not require a specific degree. It simply entails curiosity, experimentation and the ability to listen and learn from our microscopic friends.

How have you seen mainstream culture’s response to fermentation shift or evolve over the past decade?

I definitely feel like more people are fermenting at home compared to a decade ago. Fermented products have skyrocketed and I don’t think this is just a trend! We will see this interest stick, especially as more fermented products hit the shelves, more people understand the importance of a healthy microbiome (and how fermented products can help), and chefs embrace it as a method for preservation and flavor enhancement. This also means there will be more fermentation educators, books, YouTube tutorials, and so on. This has made the learning curve easier. However, I think there is still a general fear of bacteria that our society has conditioned upon us. What people really need is encouragement and simple instructions to follow. Fermented vegetables are a great starting point. Once people understand the basics of salting and submerging to create the ideal environment (and that skimming any undesirable mold or scum off the top means the bottom layers are fine!), they can unlearn their conditioning and reframe their perception of fermentation.

What kinds of misconceptions do you find that people have when they come into your classes?

The misconceptions I encounter are usually the same: People are afraid they have done something wrong when they smell something weird or experience a strange form of growth that they identify as “bad.” Since it’s a foreign process, and involves unlearning what we’ve heard about bacteria, it makes sense that people have these fears. I do my best to break down these misconceptions, and give people the simple steps needed to create a safely crafted ferment with confidence.

Are there any of your workshop offerings that have sort of been fan-favorites?

Kombucha has consistently been a hit for new fermenters. This workshop has consistently been well-attended since I started teaching it over six years ago. Within the realm of experienced fermenters, koji (a mold-based ferment that is the backbone of miso, sake, soy sauce and other Japanese ferments) has been a growing hit. I did a four-part Beginner’s Guide to Koji & Miso workshop series with a friend I met online, Marika Groen of Malica Ferments, that has gained a lot of attention. Marika is a very knowledgeable instructor from Japan (now residing in the Netherlands), and she is able to provide a great depth of information on koji. Her workshops are often very engaging and entertaining, with her pulling out random jars and crocks of different types of koji-based ferments from behind her.

What does fermentation mean to you beyond flavor?

Flavor is an important aspect of fermentation to me. However, there are so many other elements, many inspired by Sandor Katz, that I like to talk about on the subject. I believe fermenting food can help us connect to our ancestry. For those who can trace back their roots, it can help us understand how our ancestors survived and interacted with food. All cultures have some food product that is fermented, so finding what these products are can be a very enlightening way of connecting to our past.

I also believe fermenting food is one way of reclaiming the food system and developing a resilient relationship with ancient practices that have sustained us since we evolved from our primate ancestors. Fermentation brings people together and it can deconstruct the industrialized food system that has depleted our food of life and DIY practices. Fermentation brings people together and it can deconstruct the industrialized food system that has depleted the life out of live cultured foods.” Of course, there are benefits to an industrial food system, but it does not serve us in so many ways and can strip us of traditional foodways that have been so significant to our species for most of our existence. There’s also the nutrition hype that is amplifying the “live bacterial cultures” aspects of some fermented foods. I think this is a great way to bring attention to the importance of feeding our microbiome live microbes. However, I worry that solely focusing on this part of fermented foods can whitewash culturally significant foods (often from marginalized communities) and strip traditional foods of their deeper meaning for some regions of the world.

Any people or places in Pittsburgh that are special to you, or to the growth of your career?

I couldn’t be doing all of my current fermentation offerings without the presence of my partner, Jess Canose. She does most of the photography and graphic design, and supports everything I do. She also knows all the great fruit foraging spots in the urban landscape of Pittsburgh, so that’s very valuable to my Soda CSA, while supporting our personal berry eating habits. My brother, Nick, owner of Frederick SEO & Web Services, is also a huge help. He put together an amazing website for me and constantly updates it with all my fermentation happenings.

I’ve had a lot of support over the years from different organizations and friends in Pittsburgh. Oliver from Wild Rise Bakery has been a longtime fermentation friend. I was lucky enough to know him at the beginning of his gluten-free sourdough bread days, and have gotten to taste the wonderful evolution of his bakery. While he throws me experimental bread batches, I throw him my fermented veggie and miso experiments! Jayashree Iyengar of Popping Mustard Seeds is also a great friend who teaches Indian cooking classes in Pittsburgh. I spent some time in South India and was so grateful to find a friend who can make amazing dosa and idly, two wonderful grain-based ferments of Indian cuisine. She shares such a wealth of knowledge about Indian cuisine and culture with passion and enthusiasm.

Michelle Soto of Cutting Root Farm & Apothecary is a wonderful herbalist, mentor and all-around great human being. I was lucky enough to do an herbalism apprenticeship with her in 2019, and currently source almost all of my herbs from her that I infuse in my sodas for my Soda CSA. She offers so much to the community as far as herbs, medicine and knowledge go.

Justin Lubecki, founder of Ferment Pittsburgh, has also been very resourceful. He’s organized numerous Fermentation Festivals in Pittsburgh and is always fermenting weird things. He also helps spread the word when I’m advertising for a new workshop or product offering. Lastly, I’ve been a recurring instructor at Phipps Conservatory and C.R.A.F.T. and the Center for Women’s Entrepreneurship at Chatham University. These organizations have supported me in many ways, from offering me a place to teach, to providing resources to enhance my business and help me figure out the best way to transition full-time!

Any fun plans for the future to share?

My goal is to make fermentation education affordable for all people and to break down the barriers that can make this world of food preservation inaccessible. My longtime plan is to develop a worker-owned cooperative focused on fermentation education, product development and larger events. It might be a little while until I get there, but if I can have fun and make a difference in our food system and our relationship to food, then I think it’s worth the wait.

For more info on Community Cultures and Ring’s Pittsburgh Soda CSA, check out his website and sign up for the newsletter for info on upcoming workshops and product offerings!

- Photos: Jess Canose

One Comment