The land is where every wine’s story begins. Vineyard farming is a tricky, time-consuming endeavor with high stakes; a bad yield or an unexpected weather event can threaten the entire vintage of wine for the year ahead. Farming in Pennsylvania has its own challenges, with our high levels of rainfall, intense summer humidity and pest pressure. The people who do this for a living (many of whom are also winemakers) usually approach vineyard farming with a level of passion and precision that borders on obsession.

To learn more about what a winegrower’s days, weeks and months are like, we spoke with Zach Wilson, who co-owns Wayvine Winery & Vineyard with his brother James. Their 200-acre property in Nottingham, PA (in Chester County, about 20 miles southeast of Kennett Square) has been in their family for three generations. Once operated as a dairy farm, the family decided to try growing wine grapes there in 2009 after a real estate deal with a developer fell through.

Zach and James Wilson of Wayvine Winery & Vineyard

Zach explains that, right there, he’d already overcome one of the hardest challenges many vineyard farmers face: acquiring land.

“My biggest advantage was having the land to start with, as that’s the primary expense to starting any agricultural project,” he notes. “James and I did eventually buy the land from my dad and his siblings, so we do have a mortgage, but because we’re already established, it’s a lot easier to afford it.”

When Wayvine first got started, Zach was just 19 years old and James was 16. Zach was studying Business of Agriculture in college, and took an introductory workshop at a Penn State Extension office in Lancaster. Lots of Pennsylvania grape growers learn through Penn State Extension’s Grape and Wine Production program, while some learn from older generations, and others go to other universities, attend workshops or are self-taught (or some combination of all of these).

During 2009, the Wilson brothers planted a 4-acre test plot with a dozen grape varieties to see what would grow well. Test plots, plus soil analysis and evaluations with vineyard consultants are all common practices when establishing a new vineyard site.

Zach Wilson working in Wayvine’s vineyard

“That gave me something to play with for a summer before the initial planting,” he remembers. “I’m a very hands-on learner, so it was better for me to be working with grape vines and reading about them at the same time.”

After the test plot had a good yield, Zach says they “dove right in.” In 2010, they planted 3,000 vines on hilltops on the family farm. The site is on sandy, loamy soil with clay strips running through it. Through trial and error, the Wilsons learned more about their land; for instance; they initially planted some vines lower down on the hill, but soon found that the soil drainage wasn’t great and that late frosts had a worse effect in that spot.

But, in general, Zach believes that their farmland is uniquely well situated and that, thanks to the cows who grazed on the land for decades, that the fertile soil has helped their vines thrive.

“Fortunately, there’s been very little error as we’ve learned,” he says. “I’ve been totally obsessed with it the whole time; my mind never stops thinking about what the next step is, in the field, the winery, all of it.”

Among their first plantings were Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay. When the grapes began to ripen before the first harvest, the Wilsons realized there were red grapes randomly scattered throughout the Chardonnay block — a mistake made at the nursery they’d purchased from. It was a lot of fruit, nearly 10% of the plot, so they decided to make a batch of red wine with it. They loved the bold, robust and deeply fruit wine those grapes yielded.

“First, we called it ‘the mystery wine,’ but we finally narrowed it down with the nursery,” Zach says. “We figured out it was Carmine, which is Cab Sauv crossed with Carignan crossed again with Merlot.”

Carmine is now one of Wayvine’s signature reds, which they also use for blending and making rosé and sparkling wines. In fact, they’re planting 3,000 more Carmine vines this year. This is a powerful example of how wine farmers must be as adaptable, resilient and open-minded as they are regimented and disciplined.

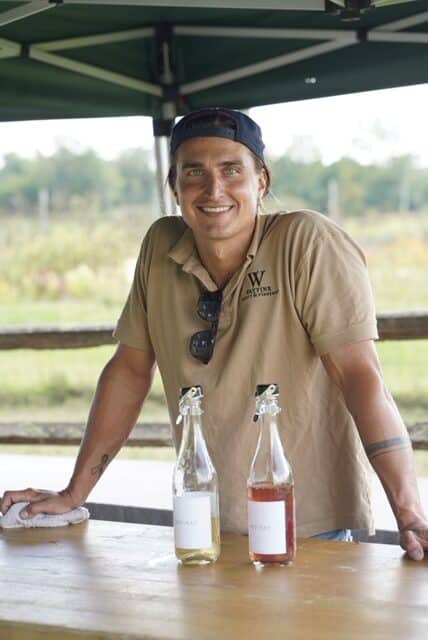

James Wilson with Wayvine wines

Most vines don’t yield fruit for about three years after planting. At Wayvine, they got some fruit a little earlier, in 2012, and made a few barrels of wine with it. Many vineyard farmers make their own wine as a value-add product to the fruit they pour so much time and energy into growing. This, ultimately, is why Wayvine became a winery in addition to a vineyard.

“Initially, we thought we’d just grow and sell some grapes, but after doing all the work and realizing how little money we’d make, we decided to start a separate venture and get our own winery going,” Zach says.

Farming a vineyard is an all-consuming process that looks different depending on the time of year. Zach breaks down the scope of his work into seasons:

- From January through March, he and his team (which includes his brother, dad and some of his uncles) are out in the fields — ideally on milder days — doing winter tie-downs and pruning. Pruning means cutting back the vines from the year before. Tie-downs are tying down the new little shoots that come off of the vines onto support trellises, and checking that the ones tied down last year are still in place.

- Mid-to-late April is bud break, when the vines begin their annual growth cycle with new green growth. The growth happens very quickly, and Zach and the team only have a few weeks to get the new buds thinned out and positioned. Positioning the new vines helps train them to grow up the sets of wires on the trellis. Then, they hedge the rows, using an extension on their tractor that cuts the top and sides of the vines. “We used to do that by hand, but it almost killed us,” Zach says.

- From late April through the summer, the grapes begin to grow. After bud break comes green shoot growth and flowering, followed by fruit set, when the fertilized flowers form small green berries that will eventually develop into fruit. As the grapes grow, they are very hard, green and incredibly sour.

The Wayvine team spends every day in the field pruning and tying, suckering (removing weak vine shoots), re-positioning shoots through each wire and pulling leaves around the fruit to increase sun exposure and airflow. “Each one of these jobs takes a solid month, with 4 or 5 of us all working by hand,” Zach notes. “By the time we get through one, we’re starting the next job.” They’re also frequently monitoring and spraying the vines throughout this time.

- Wayvine uses organic sprays and tries to keep herbicides at a minimum. The one spray that is non-negotiable, Zach says, is fungicide. Because of the rainfall levels in PA, their grapes are very susceptible to fruit rots and powdery mildew. Zach has also noticed that with climate change, summers are getting hotter and wetter, which means increased disease and pest pressure.

- Late August brings veraison, the next phase of the growing cycle. Veraison is when the fruit starts softening. As the vine growth slows down, and the vines begin to divert energy from the canopy into the fruit. More sugars form in the fruit, the acidity levels drop, and the grape skins start turning more red if they’re red wine grapes, or transparent, if they’re white. “Once that starts, you have to monitor constantly to know when you’re going to harvest,” Zach says.

- Even though the Wayvine team has consistent notes from the past decade about when to expect harvest, they still rigorously monitor the Brix and pH in the grapes. Even if grapes aren’t completely ripe sometimes they will harvest them to avoid a heat wave or potential rot issues.

- Autumn is the harvest. Wayvine’s harvest runs on volunteer-power; friends, family and folks from the community come to help pick grapes and are fed and given bottles of wine as thank yous. Other vineyards may pay staff or day laborers to assist with this time-sensitive effort.

- At Wayvine, all grapes are crushed or pressed within two hours of being picked. “I believe that as soon as the grapes are cut off the vine, the quality goes down, so that’s a huge advantage to having our own vineyards versus buying grapes and having them shipped,” Zach says.

- For winemaking, the Wilsons rely on Old World, low-intervention techniques. “A teacher once told me, ‘Treat the wine like a human being: be there when they’re a baby, but when they’re growing up, let them be on their own,’” explains Zach.

- By November, the pumping and fermentation are complete, the barrels are filled and tucked away, and, as Zach says, “Everyone is exhausted.” They get a two-month break from the fields, but that is when Zach and James turn their focus to their wholesale accounts. Then, soon after the New Year, it’s time to get back into the fields for pruning and tie-downs.

Thanks to Zach Wilson for sharing all of this info and insights about farming at Wayvine Vineyards. As we hope is made clear, it takes a Herculean amount of effort to manage a vineyard. We salute all of the vineyard farmers in Pennsylvania and thank them for their labor to produce the fruit that becomes PA Wine!

Zach Wilson vineyard farming

Find Wayvine Winery & Vineyard 5150 Forge Rd. in Nottingham, PA; phone: (610) 620-5261. Wayvine wines are also available at its sister restaurant, Tulip Pasta & Wine Bar, at 2302 E. Norris St. in Philadelphia; phone: (267) 773-8189.

The PA Vines & Wines series was created in collaboration with the Pennsylvania Wine Association with Round 8, Act 39 grant funding from the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board (PLCB).

The Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA) is a trade association that markets and advocates for the limited licensed wineries in Pennsylvania.

- Photos: Wayvine Winery & Vineyard

- PWA Logo: Pennsylvania Wine Association