If you’ve ever had a slice of bread or a spoonful of grits that stopped you, mid-chew, to wonder just how so much flavor can be packed into one bite, chances are, it all started with well above-average grains. The flour that most of us have been conditioned to think of as “regular” or “all-purpose,” and the stuff that’s in nearly all mass-produced carbs, is really just a shadow of what it could be. Most commercial flours are mega-processed, both to increase shelf stability and to give the fluffy, smooth texture that is marketed as enjoyable. But, by doing this — sifting out the germ and the bran, leaving only the endosperm in the flour — both flavor and nutritional value are also discarded.

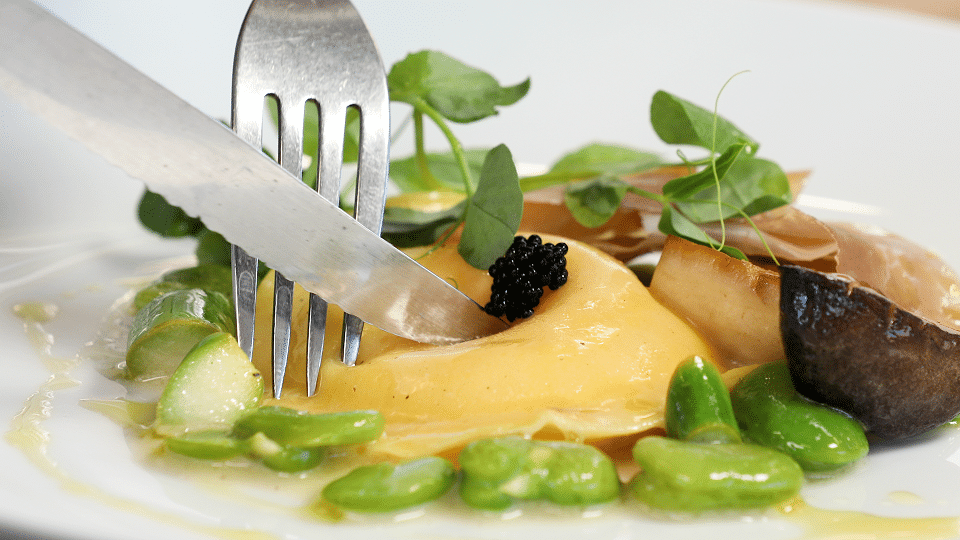

Over the past few years, there has been a quiet return to old-fashioned artisan grain milling that’s got chefs, professional bakers and savvy home cooks rediscovering the joys of freshly ground whole grain products. We’re blessed to have one such mill in our own backyard: Castle Valley Mill in Doylestown, Pa. Its grains, grits and flours can be found in some of the best bakeries in the area, including Vetri Cucina, Fork, High Street on Market and Lost Bread Co.

We wanted to learn more about the story behind the refurnished mill from the 1800’s, so we chatted with Fran Fischer, a co-owner of the mill with her husband Mark. Read on to learn more about the surprising entrepreneurial success of this homegrown company, how a stone mill works, and why Castle Valley Mill’s flour might just change your life.

PA Eats: Can you give us a quick background on the history of your company?

Fran Fischer: The short story is that we purchased this property about 20 years ago. It was the estate of Mark’s grandfather’s, Henry Fischer … his grandfather had been a miller in Germany and started working on the old mill on the property. He never got it running, but he did restore the foundation and bought a lot of parts. We’re standing on his shoulders and could never have done what we did if he hadn’t started that work.

Before this, Mark worked as an electrical engineer, and about eight years ago, he sold out of his aviation business. When he sold out, he wanted to see if he could get one of the mills running to create a little niche business. We really had no idea that we would end up on the wave of farm-to-table, we just had no clue. We got serious five years ago and threw everything into the business.

What made you decide to throw all of your eggs into this basket?

We’re amazed at what happened. We started in farmers markets, and some chefs got a hold of us and came back saying, “This is amazing.” It was a word-of-mouth thing, and we went from small to medium when we had a few distributors pick us up.

How did you all learn to become millers?

My husband is brilliant and fearless. He’s very mechanically inclined, he’s always been a tinkerer. My son is the same way. Way back, they went to a couple of millers’ training sessions offered by the Society for the Preservation of Old Mills in Tennessee, and they got certification and hands-on training.

In terms of putting the machines together and fixing up an 1800’s building, there’s no manual for that … that’s learning on the fly. I call it “forensic milling” because the machines were in pieces all over the building. The mill is a three-story building, and it used to be filled wall-to-wall with family junk and these old machines in disrepair. So, we emptied it of all the non-milling items — old couches, carpets, school books, you can’t imagine. Mark would find the basic parts of the machine, go to the U.S. Patent Office online, look up the patent number, see what it looked like and what it did and figured out how to put it back together.

How are your grains different from grains and flours we might find at the grocery store?

Our flours are live products, what you buy at the grocery store is dead. Our products needs to be refrigerated … a piece of wheat naturally contains something like 33 vitamins and minerals, but the same amount of commercially milled flour has none. They have to fortify or enrich with 8 synthetic vitamins. So, what you’re getting from the grocery store is the chalky endosperm from the wheat seed and synthetic vitamins that’s been heated, bromated, electrocuted, bleached, whatever, to get it to that state. [These companies] didn’t set out to make terrible products, they just wanted it to be shelf stable, and white, which people thought was “pure.”

If you feel our flour, it has a creamy, oily feel to it. Baking with it takes getting used to and it requires more hydration. But in terms of the end result, I’ve never heard of anyone not being absolutely thrilled. If you eat a loaf of bread made with our stuff and compare it to commercial loaves, it’s just not the same food. Our bread has flavor, while the stuff that’s mass-produced is just a vehicle to just get other ingredients to your mouth.

Can you give us a basic version of what the milling process is and what it does?

We take the entire seed and stone grind it. There are two stones, one is stationary and one is moving and it actually cuts the grain — it’s not like wine with squishing grapes. This means we take the entire component of the seed and spread it throughout the final products, whether it’s flour, grits or meal. You’re getting all of the bran, the endosperm and all of the germ, and the germ is where you get nutrients and flavors. It’s complete, it’s a true whole grain product. Commercial milling sifts out those bits, sifting out all the bran and germ so there’s none of that in final products, it’s just the endosperm.

Where are your grains sourced from?

We buy our grain from Pennsylvania farmers, we’re PA Preferred. We’re also locavores, so we try to only go within 100 to 150 miles, unless we can’t find the grain, but about but 80% is from Pa. For instance, it was a bad year for emmer farro from Pa., so we had to source from outside the state. The grain we buy is minimally hybridized … the big companies that use these monocrops, their wheat is super-hybridized wheat bred for dwarf size, disease-resistance, not for flavor or nutrition.

We have our yellow corn and hard wheat in towers, and the others we bring in and store as we need them. We triple-clean, sift out broken or cracked or unformed seeds, and clean our rocks and sticks.

Cleaning equipment

What’s a grain more people should try? What’s an approachable recipe or technique that you suggest to new customers?

I would like people to try any of our products! The easiest thing is the soft whole wheat flour. Just make pancakes at home, it’s the simplest recipe and it’s just so good, you can’t believe it. We have friends with little kids and their testimony is their kids will eat these pancakes with no butter and syrup!

Soft wheat can be used for nearly anything all-purpose flour will do, and bread makers love our hard wheat flour. Whole wheat berries you can add to soups and stews, make hot cereal, make cold salads … it’s just such good food.

Do you have an opinion about the “wellness” trend to move away from wheat and grains?

People have trouble with gluten, so many people, and we believe it’s because so much has been removed, and the hybridization has made the wheat so hard for our guts to digest. Anyone with celiac disease shouldn’t touch our stuff — I joke that they shouldn’t even touch me because I’m covered with it!

But, from gluten-intolerant people who have trouble with commercially processed wheat and store-bought bread (which often has additional gluten added to it, by the way) we have hundreds of testimonials saying they can eat all of our wheat.

To try this magical flour for yourself, check out the list of local retailers where you can find Castle Valley Mill’s products, or shop online! To keep up with the mill’s new products and occasional on-site events, follow its Facebook page.

Castle Valley Mill is located at 1730 Lower State Rd. in Doylestown; phone: (215) 340-3609.

- Photos: Castle Valley Mill

4 Comments