Food insecurity is all around us, but often invisible. People experiencing persistent hunger may not share or show it, but it quietly affects myriad aspects of life including physical, mental and social health. Recent factors like post-pandemic policy shifts and rising costs of living have only exacerbated the issue, which is tackled on federal, state and local levels. Learning more about food insecurity and the programs in place can allow us to take steps toward solutions as neighbors, voters and Pennsylvanians.

Defining Food Insecurity

What, exactly, is food insecurity? Feeding America defines it simply as “when people can’t access the food they need to live their fullest lives.” It’s a persistent condition experienced by households and driven by various economic and social factors. The primary drivers of food insecurity include poverty, unemployment, low-wage jobs, lack of affordable housing, chronic health conditions, racism and systemic discrimination.

Food insecurity differs slightly from hunger in its definition, though the two are closely intertwined. Food insecurity is an ongoing lack of certainty about one’s next meal, which can lead to hunger among other physiological conditions like stress.

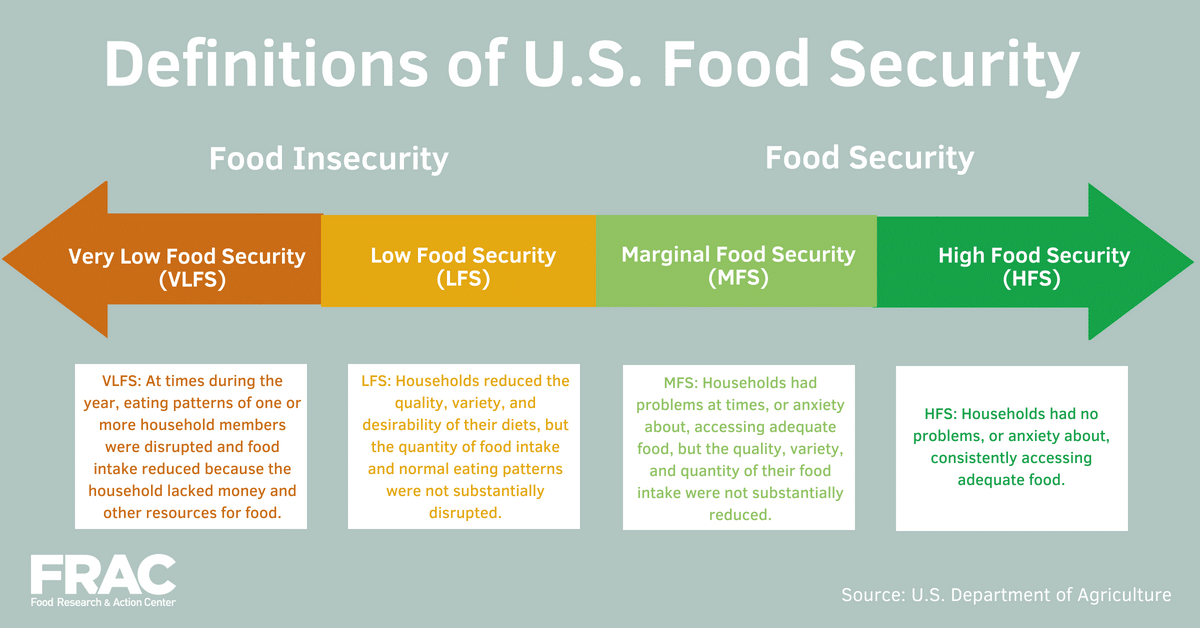

The USDA orgnizes food security and insecurity into four categories, ranging from most to least food secure. Food secure individuals may experience anything from zero problems with food access to some limited anxiety over food sufficiency. Food insecure individuals can experience reduced quality, variety or desirability in their diet or multiple occasions of reduced food intake and disrupted eating patterns.

Food insecurity impacts one’s entire well being. On a physical level, it leads to malnutrition and chronic conditions. It also undermines mental health, contributing to stress, anxiety and depression. Food insecurity also has tremendous social impacts. It can cause feelings of shame leading to social isolation as well as trouble concentrating or participating fully in work or school activities and tasks.

Food insecurity is not always obvious, but there are some signs that may point to the condition. In children, food insecurity can lead to talking about food frequently along with hoarding behaviors, low attention span, trouble with memory, aggression and sudden changes in weight including dramatic loss or gain.

By the Numbers

According to Feeding Pennsylvania, over 1.5 million Pennsylvanians experience food insecurity, and people in every single PA county battle hunger. That is every one in eight people, and one in six children. There are 436,000 children experiencing food security in the state. The odds are high that you encounter food insecurity on a regular basis, whether it’s obvious or not.

Rates of food insecurity vary across Pennsylvania, with with rates as low as 8.1% in Chester County in SEPA to a high of 16.8% in rural, northwestern Forest County. It is typical for rural areas to experience disproportionately high levels of food insecurity. The state-wide rate of food insecurity is 11.9% (16.9% for children), while the national rate is 12.8% (19% for children).

Food is expensive. The average cost of a meal in the U.S. is $3.99, the highest its been in twenty years, even after adjusting for inflation. In Pennsylvania, it’s risen to $4.05. Household grocery costs often average around $250 – $330 every week, depending on location and household size. Of those facing hunger in Pennsylvania, only about half qualify for SNAP federal assistance. The national food budget shortfall, which is the money that people experiencing food insecurity would need to bridge the gap to food security, is the highest it’s been in twenty years at a record high of $33.1 billion.

Historical, social, economic and systemic barriers that hold back communities of color also result in disproportionate food insecurity rates among Black and Latino individuals, which are 27% and 25% in Pennsylvania, contrasted with 9% among White residents.

In Pennsylvania, there are 18 food banks in that distribute over 164 million pounds of food per year to 2,700 agencies, eeding programs and food pantries.

SNAP and Other Programs

The federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly called food stamps, is the largest anti-hunger program in the country, providing over 40 million people with financial support. Those who qualify receive monthly funds in an account through electronic benefits transfer, or, EBT. Those funds can be accessed with a debit card (also called the EBT ACCESS card), which can be used to pay for groceries at local stores and farmers markets. More and more PA markets and vendors and even online delivery companies are accepting SNAP, allowing for greater access to fresh food.

Anyone can apply for SNAP. Unfortunately, though, nearly half of the people facing hunger in the U.S. are unlikely to qualify for this federal program. For example, a family of four with a household income of $65,000 could exceed the qualification threshold. Nonetheless, the program is at a record high use in Pennsylvania, with over 2 million residents participating.

SNAP can be used for fresh produce, meat and fish, dairy, breads and cereal, snacks, beverages and plants to grow your own food. It does not cover products like alcohol or cigarettes, household supplies, vitamins or medicine.

There are a number of other federal food assistance programs that seek to support various groups and needs. WIC is aimed at supporting the vulnerable population of low-income pregnant and postpartum women and their children, infant through age five, who are at nutritional risk.Its full title is Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Mothers and children receive supplemental foods, nutritional education and health care referrals. The services are accessed through county health departments, hospitals, community centers, schools, and other local sites.

Children are also eligible to receive free school breakfasts and lunches, as well as meals and snacks throughout the summer through the The School Breakfast Program (SBP), The National Lunch Program (NSLP) and The Summer Food Service Program (SFSP). Food is also available in care centers through The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP).

Families experiencing crisis or emergency can find short-term hunger relief through The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) and low-income seniors can qualify for monthly food assistance through The Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP).

Other, state-level resources in Pennsylvania include PA 211, a direct line to emergency relief through United Way, thousands of charitable food bank partners, the Senior Food Box Program, the Pennsylvania Agricultural Surplus System that incentives donation of extra food products, State Food Purchase Program grants, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families cash relief.

Legislation

The pandemic brought about severe issues with food access and, in response, federal relief. As those programs and temporary allotments taper off while inflation elevates food prices, we are seeing rises in food insecurity across the country.

There are many policies and programs on federal and state levels to keep an eye on, which greatly impact how food insecurity is addressed. Three major policy suggestions by Feeding America include:

- Expand and strengthen SNAP. While highly impactful, this program has room for improvement. Specifically, its coverage could better meet modern food costs and needs, and it could reduce barriers to access. SNAP benefits did not cover the cost of a meal in 99% of counties in 2022. The Average meal in Pennsylvania costs $4.05. Additionally, millions of people experiencing food insecurity do not qualify for SNAP, with incomes above the threshold, complicated application processes and restrictions like the Federal Drug Ban.

- Simplify and improve access to other food assistance programs. School programs can reach more students, year-round, with streamlining, expansions and strong implementation. Additionally, Native American communities would be better served if tribal governments could administer federal programs. Also, more funding and reauthorization for TEFAP and CSFP would improve food access, particularly in rural communities and for seniors.

- Improve policies that support financial well-being. At the heart of food insecurity is financial insecurity. Affordable housing is one area of direct impact, which includes how landlord oversight is handled. Benefit cliffs, like losing SNAP eligibility as soon as you earn a wage increase, should be eliminated. And Feeding America suggests permanent expansion of The Child Tax Credit, which gives families financial breathing room and has lifted more children above the poverty line than any other economic support program.

On a state level, Feeding PA is calling for better funding of food assistance programs, which received flat funding of state nutritional programs in the 2025 budget. Julie Bancroft, CEO, said in a statement, “Despite a $14 billion budget surplus and on the heels of new data from Feeding America’s Map the Meal Gap report showing a twenty-five percent increase in food insecurity across Pennsylvania, neighbors experiencing hunger have been left behind.”

Additionally, keep your eye on the Farm Bill, currently overdue but expected to pass in September, 2024. In a statement on the bill, Bancroft says, “We have an opportunity in the Farm Bill to address the reality of hunger and food insecurity facing children, seniors, and families in Pennsylvania and across the Nation so all have the healthy, nutritious food they need to thrive.” Despite some key improvements, a recent draft of the bill includes oversights that may impede how SNAP benefits keep pace with real-world food needs. It also lacks adequate funding for TEFAP, which is needed for food banks to serve the need in their communities through food purchases, storage and distribution. You can take action and ask Congress to pass a stronger Farm Bill.

What You Can Do

Hunger and food insecurity are community issues that require community solutions. Learning more is the first step.

If you’re experiencing food insecurity or want to take action in addressing hunger, we suggest contacting your local food bank or pantry. People there can point you in the right direction. Feeding Pennsylvania also provides a food bank locator and great starting points for action including how to volunteer, ways to donate and how to use your voice.

For more ideas, check out PA Eats’ 8 Ways to Be Part of Hunger Action Month.

- Infographic: U.S. Department of Agriculture via Food Action and Research Center

- All other photos: Bigstock