When your state is home to the “Mushroom Capital of the World,” chances are you’ve driven by a mushroom farm before. You’re usually alerted first by that, um, distinctly pungent smell before you see the large, industrial warehouses with mountains of black soil outside. But, just as there are all sizes of vegetable farms ranging from massive to mini, so too are there mushroom farms in Pennsylvania working on a much, much smaller scale than the huge operations in Kennett Square. One such micro-mushroom farm is Fungus Aurelius, the project of James Coleman, an ex-restaurant chef and current private chef.

Tucked into a patch of forest in Lancaster County, Fungus Aurelius is as DIY, artisanal as it gets: Coleman started in 2020, growing mushrooms on a shelf in his garage, and from there, he built out a greenhouse and small production pavilion on his property in 2021. He does his own lab work, makes his own blocks of substrate (more on that later) and packages and takes everything to market himself.

In talking with Coleman, we went deep into the mysterious world of mycelium, and learned more about what it’s like to commune with and work with microscopic entities. Check it out in this Meet the Farmer Q&A:

PA Eats: When did you first take an interest in growing your own mushrooms?

James Coleman: I have been a chef for many years; I started cooking when I was 17, and now I’m 41. Sometime in my 20s, my mind started to wander and I would think, what else could I be doing? I don’t want to say anything negative about my chef jobs, but it’s a very stressful industry. The restaurant I worked for started sourcing from local farmers and that piqued my interest about how some of my favorite ingredients were produced. Eventually, I realized that I wanted to create my favorite ingredients, instead of create with my favorite ingredients.

Thirteen years ago, my wife and I moved here to Lancaster County for agricultural purposes. Initially, I really wanted to have a goat herd and start my own dairy, but there’s a lot that goes along with that. You pretty much have to become a meat farmer, which I didn’t want to do. Because we live in this old growth forest with so much shade, I knew that we wouldn’t be able to grow vegetables. I’d see mushrooms growing on trees and branches that came down periodically, and it just kind of clicked to give mushrooms a try.

Did you teach yourself how to become a mushroom farmer?

In 2019, I went to a mushroom farm in British Columbia, What the Fungus, for a mentorship program. You go camp out there for a week, and by the end of the week you’ve learned how the farm works. What I’m doing here is basically mirroring their processes.

I’m still always learning, it’s constant. There’s so much observation that goes into this process, and it’s very labor-intensive, considering I’m doing everything by myself.

Can you walk us through what it actually looks like to grow mushrooms the way you do?

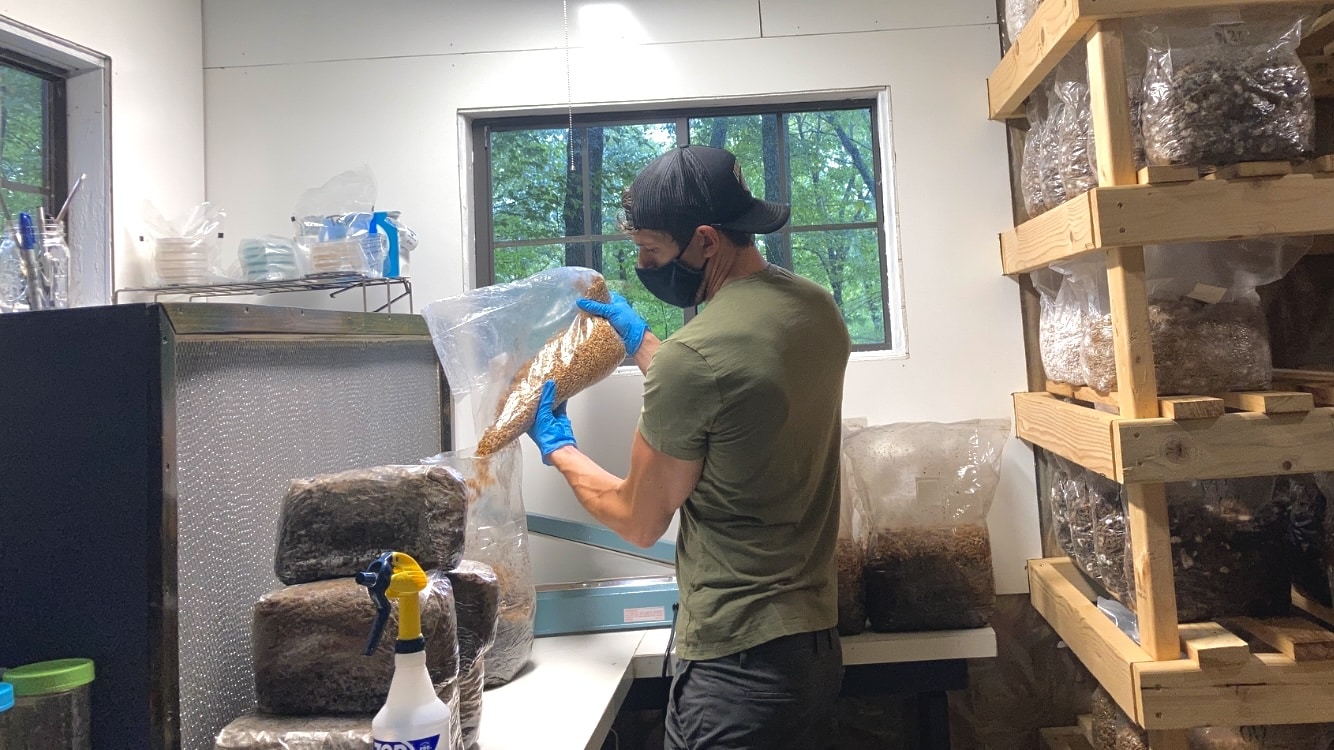

The beginning of my growing process happens in petri dishes in agar in my lab, which is a sterile work environment. I have to sterilize and pasteurize all my growing mediums. Right behind where I do my lab work are long shelves where I put the inoculated bags of substrate or grain spawn that I colonize. The substrate is sawdust or wood chips, which gets joined together by the mushroom mycelium and it turns into a block. Some people buy pre-inoculated blocks, but I make my own. I do that because one of my biggest challenges is contamination, from either other bacteria, mold or fungus in the substrate. If that takes over, you won’t get the yields or be able to make anything happen. If I’m buying blocks made elsewhere, there’s nothing I can do if they’re contaminated. But if I’m making them, I can kind of take a step backwards and find out where the vector of contamination is. I’d rather take on that responsibility doing it all myself.

I built a little pavilion with work tables, where I make those substrate bags, and I do my pasteurization there. Once that’s done, that gets moved into the lab and then goes into my greenhouse, which is a small 10-by-12-foot structure I built where I control the air flow and humidity. Depending on the temperature, I change what mushroom I’m fruiting. There are some that like it colder in spring and fall, and ones that prefer warmer temperatures in the summer. I’m seasonal like that.

Is there something specific about farming mushrooms that you’ve come to enjoy or appreciate?

What I really love about this process is that what I’m ultimately creating is rich, composted topsoil, and mushrooms are just a byproduct. When I first moved here to this forest, when a tree fell down I’d cut it up and use it to burn in our wood-burning stove. I took so much of what I imagine to be this forest’s food sources, because that’s ultimately what the wood is for the fungus. Growing mushrooms is what I can do to give back to this forest.

What kinds of mushrooms does Fungus Aurelius grow?

The mushrooms are feeding, saprotrophic mushrooms, and they break down organic matter. Mycorrhizal is the other kind, those are mushrooms like morels and chanterelles, that create symbiotic relationships with other plants. But saprotrophic mushrooms are recycling everything. I can keep growing mushrooms on the wood chips outside, and over time, they take all the nutrients out. The wood is going to decompose within a year, and I will have a mound of pure black topsoil.

I grow a lot of oyster mushroom varieties, in an effort to try to find what does the best here in my conditions. I enjoy growing Lion’s Mane. I’ve tried chestnut mushrooms, which are really unique, beautiful mushrooms that I came across in Canada. In the future, I’d like to grow more medicinal mushrooms, like reishi and Turkey Tail, and to make some more value-added products, too.

Working with fungus, spores and bacteria all day seems like a pretty mysterious kind of farming. What’s it like for you?

Think of it this way: When you see a mushroom growing in the wild, that’s a one in a million, considering the amount of spores they release and the scale that they move, and how the the threads of mycelium are moving slowly underground with the millions of competitors it’s got to battle.

In a farming sense, there are a number of ways to begin growing mushrooms. Starting with spores is one way, but since they’re produced in outdoor conditions, they are microscopically dirty. In my lab, I need the petri dish to only contain mushrooms. If one gets contaminated, I’d try to take a clean portion, like the size of a grain of rice, and transfer it, and keep doing that until it’s clean. That takes a few weeks! I could also order from a company that makes these petri dishes in labs, and there’s also liquid culture, like a SCOBY for kombucha.

I can also clone things in my lab. I break open the mushroom, expose an internal part that hasn’t been exposed to air, then take a tissue culture and grow it out on a petri dish. Cloning is a way of isolating a mushroom’s genetics, while spores just reset the gene. If I bring mushrooms home from Canada, it’s the same genes that keeps growing out. If I have a petri dish I can get 100 rice sized pieces and grow all those out. There are like a million pounds of mushrooms you can expand from one petri dish. Mushrooms are almost immortal; if there’s a food source, they’ll just keep growing. That’s part of this fascinating organism!

You can find Fungus Aurelius every Sunday at the Berwyn Farmer’s Market. For news, updates and events, follow them on Instagram and Facebook.

- Photos: Fungus Aurelius

3 Comments