Maple syrup is a magic substance. Literally, the food that maple trees use to feed themselves and their little buds, it’s the closest thing we really have to the nectar of the gods, a liquid that teems with the life and energy of the forest. In cold weather, these stately trees store starch in their trunks and roots to prepare for winter. Given the right temperature conditions in later winter and early spring (below freezing at night and around 40 degrees Fahrenheit during the day), the starches convert to sugar and the sap begins to flow. Why the sap flows is still a bit of a mystery, involving complex science around temperature, suction and pressure. But the process of making syrup is pretty simple: Anyone with access to a maple tree can drive a small tube, called a spile, into the tree to collect the sap, which is then boiled down into maple syrup.

Maple trees are indigenous to North America, and while there is a tiny bit of production in Japan and South Korea, the vast majority of maple syrup is made in Canada and the Northeastern part of the United States. Think about that — in the grand scheme of things, Pennsylvania is one of only a few places in the world where maple syrup is made. That’s pretty amazing!

When it comes to production, Canada is responsible for over 80% of the world’s maple syrup production, with Quebec making up about 90% of that number. In the US, which as a whole produces around 4.16 million gallons each year, Vermont is the leader and Pennsylvania’s rank shifts between fourth and seventh, depending on the year. According to the PA Department of Agriculture, our Commonwealth produced produced 178,000 gallons in 2020, 168,000 gallons in 2021 and 164,000 gallons in 2022, all from around 250 producers.

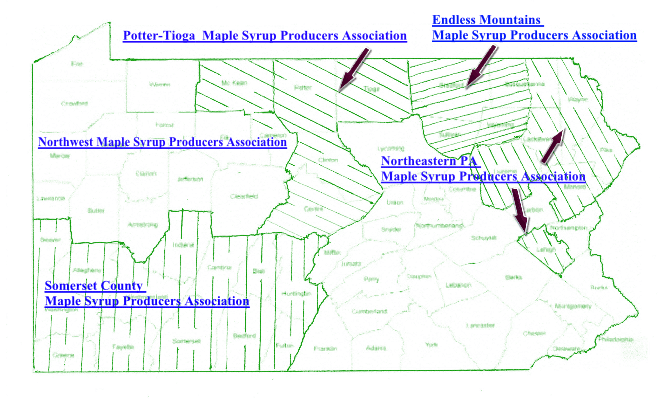

Like many agricultural communities in PA, there is an organizing body around the many producers: the Pennsylvania Maple Producers Council. The Council is made up of five member associations that stretch all across the northern and western parts of the state: Northwest Maple Syrup Producers Association, Potter-Tioga Maple Syrup Producers Association, Northeastern PA Maple Syrup Producers Association, Somerset County Maple Syrup Producers Association and Endless Mountains Maple Syrup Producers Association.

Though maple syrup can be harvested from red and black maple trees, the sugar maple has the highest concentration of sugars. Pennsylvania is blessed with an enormous population of sugar maple trees, which were first tapped for syrup and sugar by indigenous peoples who lived here hundreds of years ago. Early colonizers were shown their methods, and evolved them into the Industrial Age. Now, the process is somewhat more technologically advanced, but the core methodology remains the same: Tap the tree, collect the sap, boil the sap into syrup.

Patterson Farms

At Patterson Farms in Westfield, PA (Tioga County), the Patterson family has been harvesting maple syrup for five generations. Currently, they are the largest producer of maple syrup in Pennsylvania, with over 75,000 trees tapped across its own property, and 24 other plots that it rents. Mary Lee Zechman, Patterson Farms’ Southeastern PA Sales Representative, and sister of Richard Patterson, the family member who was running the business until he passed away in 2018 (it’s now run by his nephew, Terry Patterson, and his wife, Terri). Zechman says that her grandfather bought the farm in 1920, and during that time, all of the neighboring farmers would tap the maple trees on their property to help feed their families and provide some supplemental income.

“My grandfather made enough from our land for the family use, and if he had a little extra, he bartered with it at the local store for his groceries,” she says. “After father took over in 1944, when it was time for us to get new shoes for school, we went down to the general store and would trade the syrup for them!”

Zechman’s Grandfather tapped the maple trees with wooden spiles that he whittled out of sycamore trees, and used wooden buckets to collect the sap, which were brought back to the sugar house by a horse and sleigh. In the 1940s, her father upgraded to metal stiles and galvanized steel buckets, and a tractor instead of horses. When Zechman and her brother Richard took over, they began to use plastic stiles, which are smaller and allow the tree to heal more quickly. They also use plastic lines, which are like hoses that runs from tree to tree and collect all of the sap into big stainless steel tanks.

The stainless tanks are loaded onto trucks, many of which are repurposed milk trucks. The sap is taken to a sugar house which is also on their property.

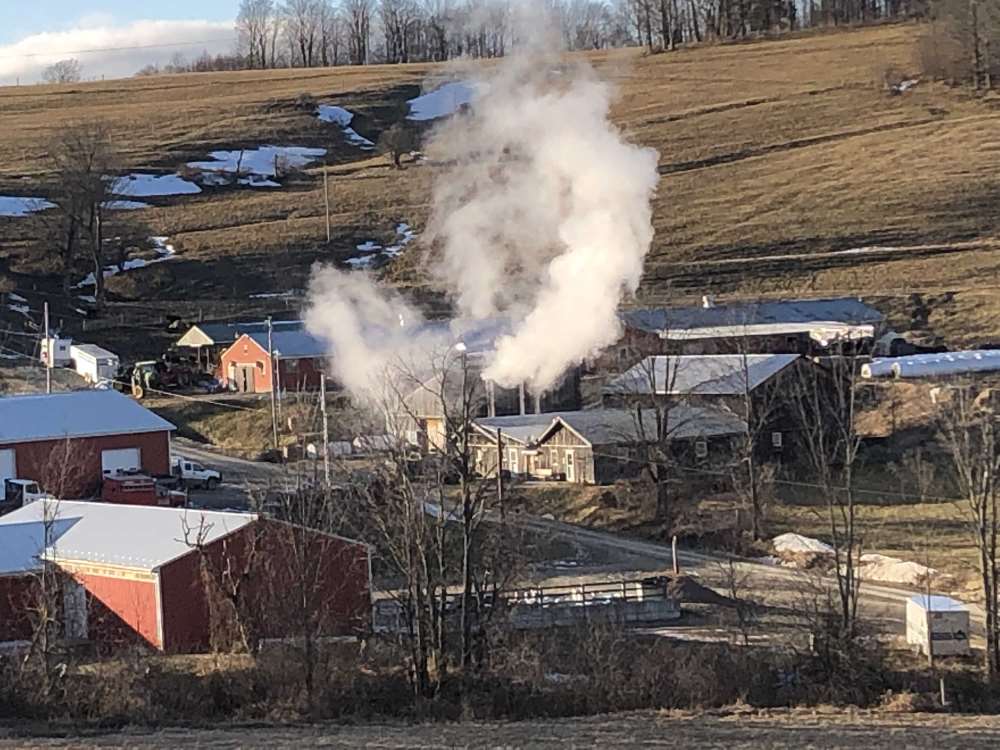

Back in Zechman’s grandfather’s time, the sap was boiled over a live fire, but now a large stainless steel turbo evaporater does the cooking. This machine does the work of boiling in 1 hour, compared to the 18 to 24 hours it used to take over a fire!

Once the sap is hauled in, it’s quickly fed to the evaporator and boiled off, and the syrup is automatically drawn into big stainless barrels, where it’s sealed up and held until it’s ready for canning.

“We don’t hold our sap, and we don’t can anything up until we sell it, so nothing is sitting on a shelf and everything is put up fresh,” Zechman says. “We also don’t add any preservatives, so our maple syrup must be refrigerated!”

All told, it takes 40 gallons of sap to makes just about 1 gallon of syrup. The sap, which is 2% sugar and 98% water, tastes likes lightly sweetened water, tasty and refreshing, but lacking in flavor. The boiling process reduces the liquid until the concentration is 65% sugar.

“It takes a lot of fuel and a lot of boiling, there’s a lot of labor and love in it,” says Zechman. “And when you go into the sugar house, it smells heavenly! There’s also all that steam that looks so pretty as you drive past.”

Just like other agricultural products, like honey and wine, maple syrup conveys the terroir of its place of origin, due to weather and soil composition. That means that maple syrup from Vermont is not going to taste like maple syrup from Pennsylvania. Some people who travel like to collect bottles from all the places they go to compare the different flavors.

“Of course, I think that PA syrup has a wonderful flavor, very mild and delicate, and it’s so smooth at the finish. You could drink it right out of a cup!” says Zechman.

As you’ve probably seen in grocery stores, there are four different grades of maple syrup. Their difference doesn’t come from how long the sap boils, but from what point in the year the sap was harvested from the tree! The different grades are:

- US Grade A Golden: Light in color and delicate in flavor. This is from the sap that comes first in the season. At Patterson Farms, they use Golden syrup to make maple candy and cream.

- US Grade A Amber: Rich maple flavor that makes a good table syrup, which is from the early-middle of the season.

- US Grade A Dark: More robust in both color and flavor, which is from the middle-late part of the season.

- US Grade A Very Dark: A very strong flavor, which is from the end of the season. Traditionally used for baking, not table syrup.

But Zechman says she sees that changing. At farmer’s markets, and other places where she samples Patterson Farms maple syrup, she says the younger generation shows more interest and enjoyment in the bold, flavorful taste of Very Dark syrup.

“I find that people’s taste is moving up to the dark and the very dark,” she notes. “They say, ‘If I am going to taste maple syrup, I want to taste it!'”

Patterson farms makes a number of products besides syrup, including maple cream (amazing on English muffins and toast), maple candies and maple sugar. Maple sugar is what you get when you’ve boiled all the water out of the sap. Zechman says she sells it to a few fine dining restaurants which grate it over fruits and vegetables, and that it’s popular with campers, hikers and runners for its lightweight, easy-to-pack convenience.

The maple sugaring season at Patterson Farms stars early in the the winter, when crews go out into the woods to start cleaning up limbs that might have fallen and check for any damage that’s been made to the lines.

“Porcupine are the worst, they love to chew on the plastic lines!” Zechman reports.

The crews repair the lines by splicing in new pieces of plastic, which can take a good deal of time with as many lines as Patterson Farms has. Then, the crew begins to tap the trees, one at a time, with a battery powered drill that drives the plastic spiles just about 3/8-inch into the tree. The holes must be re-tapped into a new part of the tree every year, as the bark grows over the old hole (the trees are not damaged). Once all of the lines are repaired, the Patterson Farms team can keep an eye on their condition with a video surveillance system they’ve installed across their properties.

How long the sugaring season lasts all depends on the weather. Once spring comes and the buds starts to swell, the trees reserve all their sap for the new growth ahead.

“The tree will never give you more than it can without harming itself,” Zechman notes.

Usually, the season lasts from the beginning of February through March, but Zechman says that she’s seen the weather patterns shift dramatically over the course of her life. When she was a child, her family would start boiling in January, and there would be deep snow on the forest floor.

“When I was in college, the whole crew had to have snowshoes to get into the woods, and now our shoes hang on the wall of the sugar house,” Zechman remarks. “I can see maple syrup going extinct someday, and that would be pretty sad.”

We hope that isn’t true, but just like all of the other agricultural communities in the state, country and around the world, climate change and unpredictable weather patterns can have huge and sometimes devastating effects. While the maple trees still grow tall and their sap runs freely, be sure to support your local maple syrup producers! Patterson Farms is open year-round and offers tours, where groups can see the production facility and say hello to the herds of cows and flocks of hens that also live on the farm. Its on-site shop sells all of its products (also available online), and its products are also available throughout PA in places like Lemon Street Market in Lancaster and The Country Store in Mount Joy.

If you’re looking for a maple syrup farm or sugarworks in your area, the Pennsylvania Maple Syrup Producers Dashboard is a great place to start. And if you’re keen to dive deeper into the world of PA maple, save the date for the annual Pennsylvania Maple Festival in Meyersdale, PA. Hurry Hill Farm in Edinsboro, PA is home to a Maple Museum, which features works centering on the art and science of making pure maple syrup, as well as maple syrup’s history. And don’t forget to check out Visit PA’s Maple Trail, a two-day road trip that will take you to some of the most maple-minded places in the state! There are also tree-tapping and sugaring events all over Pennsylvania, including some at state parks, where you can talk to maple farmers and watch a scaled-down version of maple production.

Next time you pour syrup on your waffles or pancakes, give a moment to think about all that had to go into that lovely amber liquid. Shop local, and support PA farmers to keep this amazing PA product flowing! For fun, unexpected ways to use Pennsylvania maple syrup, check out our recipes for Vegan, Gluten-Free Maple Tahini Cereal Treats, PA Corn Cheddar, and Chive Waffles with Tomato Maple Syrup and PA Chestnut and Brussels Sprouts Salad with Maple Vinaigrette.

Find Patterson Farms at 119 Patterson Rd., in Westfield, PA; phone: (814)-628-3751.

- Maple harvesting and sugar house photos: Patterson Farms

- Tree tapping event photos: Mary Bigham

- PA State Map: Pennsylvania Maple Syrup Producers Council