Tucked into a historic home on the Main Line in the Philadelphia suburbs is a hidden treasure. Its contents hold information about our region just as valuable and informational as centuries-old paintings or well-preserved texts. The Roughwood Seed Collection, the oldest private seed collection in Pennsylvania, is a botanical bounty of over 5,000 varieties of heirloom food plants, many of which were previously thought to have been extinct. Carefully tended to in the Roughwood House, this vast library of seeds creates a tangible bond between the present moment and the people who have inhabited these lands, stretching back to Native American tribes.

The Roughwood Seed Collection began in 1932, an informal project by H. Ralph Weaver, who worked to acquire heirloom seeds to help feed his family during the Great Depression. This West Chester resident leveraged connections he’d made with family members in Lancaster County through genealogy research to amass a number of seeds that had been passed down through Dutch Country for generations. By the 1940s he was the owner of a robust kitchen garden.

In the mid-1960s, about a decade after H. Ralph’s untimely death, Dr. William Woys Weaver, a PA-based food historian and author, found his grandfather’s seed collection in the bottom of a deep freezer. He began to catalog and grow this collection of rare and heirloom plants and named it the Roughwood Seed Collection, named after his circa-1805 home in Devon, PA, where the collection has been housed since 1979. This incredible seed bank carries on H. Ralph Weaver’s legacy, literally one plant at a time, bringing forth a jaw-dropping array of fruits and vegetables from the dormant seeds. These plants are grown at Roughwood, as well as a one-acre garden site at a private home in nearby Bryn Mawr, PA and at numerous satellite garden sites, tended to by volunteer growers.

The Roughwood Garden in Bryn Mawr, PA

The collection is currently managed by Stephen Smith, a Tennessee transplant who Dr. Weaver says has, “singlehandedly saved the collection and moved it forward for the good of Pennsylvanians everywhere.” He’s been working with Roughwood for almost three years; an avid seed saver since the age of 10, Smith had already been aware of Roughwood, and Dr. Weaver was one of his idols.

“Both of my parents are retired plant breeders, they did that for over 30 years, traveled the world and everything,” Smith says. “My parents always had a nice garden every year where they grew their own vegetables. They always had me out in the garden, and I’ve been gardening since I was three years old.”

Stephen Smith

Smith, who is of Cherokee and Creek ancestry, is the owner of the largest non-government collection of corn in the United States. He has over 2,500 varieties of corn from all over the world, many of which people have sent him, from North, Central and South America, Africa, Eastern Europe and other locales. He first met Dr. Weaver in 2016 at the Baker Creek National Heirloom Expo in Santa Rosa, California.

“I tell people, for me it was like I met Oprah or something because I admired everything he did, his knowledge and the preservation within the Roughwood Collection,” Smith remembers.

Smith’s mom Dorothy, Dr. William Woys Weaver, Smith, and Jere Gettle (Founder/Owner of Baker Creek Heirloom Seed Co.) at the 2016 National Heirloom Expo

The following year, Dr. Weaver emailed Smith a question about corn and the two struck up a correspondence. Smith mentioned on a whim that he’d love to work with Roughwood in the future, and Dr. Weaver emailed him back and inviting him out over his Thanksgiving break (Smith was still a college student at the time, studying agricultural crop breeding and genetics). Smith visited Roughwood and interviewed for a position as collection manager.

“He really wanted me to start right then and there, but I wanted to get my bachelor’s degree first,” Smith says. “So in May of 2018, about 4 or 5 days after graduation, I officially moved here to PA to take the position and I’ve been here ever since. I was thrilled! Even in the really hard moments we have, I always think back to that first moment, it brings me so much joy to be able to do what I do.”

What Smith has been tasked with doing is stewarding the seed collection, over 5,000 varieties of medicinal plants, herbs, heirloom vegetables and other edible flowers from all over the globe. The seeds are kept in a cool storage room at the Roughwood house, organized in paper envelopes labeled with the seed’s variety, ID number and the year or date when they were last grown. The packets are kept safe in a glass jars, organized by what type of crop they are.

“There are so many varieties, we can’t grow everything,” Smith says. “People still send stuff and we always try to tell people that if they have heirlooms, we’re always happy to accept donations. We love adding to it as much as we can!”

People are indeed always donating or sending in interesting — and sometimes mysterious — seeds, many of which require some sleuthing to identify. Smith recalls a woman who gave them tomato seeds that had been in her family for decades, which she said looked like a big red strawberry when grown but didn’t know much else about it. Smith and Dr. Weaver began researching what kinds of tomatoes were in circulation 40 or 50 years ago, and determined that it was a local selection, a Strawberry Oxheart tomato.

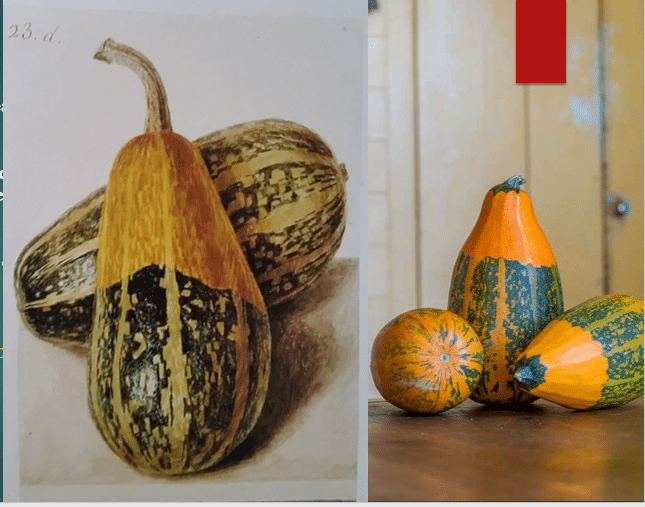

Smith shares another story from the mid-90s, when Dr. Weaver gave a lecture in New Jersey, a woman in the audience gave him a baggie of squash seeds, saying that they were very rare, old and that it was important that someone keep them going. Dr. Weaver gave her his contact info but she never reached back out to him.

“Fast forward to about this time last year, and William was researching this lady again. The squash she gave him turned out to be over two dozen different types of pre-Columbian squash varieties that would’ve been grown here long before the English came over,” Smith says. “They hadn’t been seen since the late 1600s.”

Bear Path Squash

They identified the squash thanks to an 18th-century French botanist, Antoine Nicolas Duchesne, who was obsessed with squash from North America, which he grew in France in his greenhouse, and he painted. Roughwood owns a rare book of squash paintings by Duchesne, and were able to compare the some of the squash grown by the mystery seeds with a painting of Bear Path Squash in the book. The plot thickened even further when Dr. Weaver found the obituary of the woman who the seeds had come from; not long after she’d given him the seeds, she passed away.

“She was part of the Nanticoke nation … She was one of the wisdom keepers,” Smith notes. “These particular squash she gave him were some of the original squash of the indigenous people that were here in this region.”

Though they were able to piece together the information in those cases, Smith says that there are other seeds in the collection that have been there for years and they still don’t know anything about them.

“But information comes to us one way or another, it’s usually a matter of time,” he adds.

To see what becomes of the Roughwood seeds, they are planted in the Bryn Mawr garden space. The garden is to keep the seeds going, and once the plants are grown, Smith is able to photograph everything and take notes on what the plants look like, when they flower and what they taste like. So far, Smith estimates they’ve planted about half of the seeds in the collection.

“Every time we plant it’s always exciting, it’s always something new,” Smith says. “A lot of the old tomatoes that I’ve grown out, I’m just blown away at how productive they are. These are tomatoes that not only have been considered extinct since the 1800’s, they were varieties people were breeding back then. It blows me away how vigorous they are, even with the way the modern climate has become.”

Smith is endlessly inspired by the amount of diversity that springs from these heirlooms seeds, by the dozens of colors and shapes that come out of squash, beans and greens seeds. Some of the kale and lettuce that Dr. Weaver has saved at Roughwood dates back from the Medieval period, and Smith muses that, “a lot of the plants that we humans eat are much older than we probably think they are.”

“For us, it’s literally like we’re eating a part of history. It is amazing to have the opportunity to eat these things that have been extinct or are just so old … biting into a 200-year-old tomato, not just anyone can do that!” Smith says. “But in another sense it’s kind of sad … a lot of things have just been forgotten and replaced by modern hybrids.”

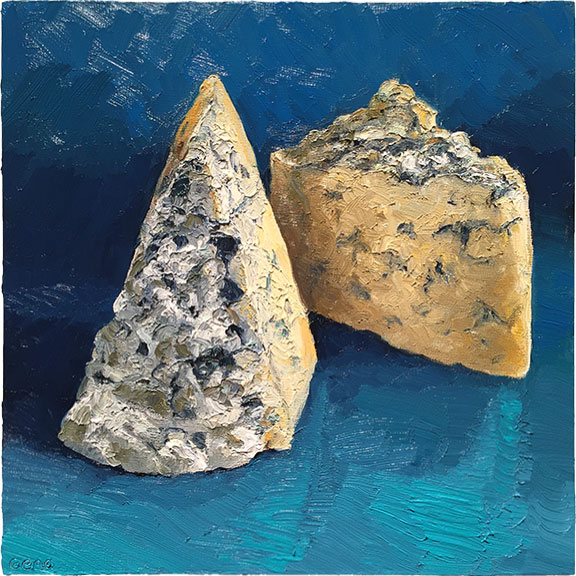

Lemon Blush Tomatoes and a Tomato Peach Pie

One of the most memorable things that Smith has gotten to experience is a tomato called Thorburne’s Lemon Blush. It was was bread in part of New Jersey in the 1800s and had not been seen since the early 1900s. The tomatoes are a beautiful bright lemon yellow color, with a big of red blush on their bottoms. Smith had been looking through old Thornburne Company seed catalogs, and when he got to the Lemon Blush, he showed it to Dr. Weavers.

“William said, ‘We have that one,’ and I said ‘But it’s extinct!’” Smith remembers, “And he said, ‘Not anymore.’”

Turns out that Dr. Weaver had been given an envelope of these seeds from a man in New Jersey in the 1980s. Smith grew them in 2018, and says biting into one is like a slice of lemon meringue pie, sweet, fruity and not as acidic as other tomatoes. After they saved the seeds from them, Dr. Weavers turned the excess fruit into an old PA Dutch recipe for a yellow peach and yellow tomato pie (pictured above).

The garden at Roughwood House

The Roughwood House is home to some old fruit trees as well as Dr. Weaver’s dahlia collection, full of many varietals that have been extinct since the 1800s, including edible dahlias, which have ginger-y tasting roots.

A Victorian Dahlia bred by Dr. Weaver

The garden’s harvest can be robust, and what the Roughwood team doesn’t eat is donated to local food banks. Dr. Weaver also uses the produce grown there to develop the historically inspired recipes in his cookbooks. They are also working on getting more Roughwood produce into local restaurants, and have already been partnering with Chef Adam Diltz of Elwood in Philadelphia.

Smith has also helped Roughwood register as an educational nonprofit, Roughwood Table, and is hoping to host garden tours, education programs and workshops at the garden. Their goal is also to able to raise money to provide grants for seed savers, gardeners, farmers and indigenous people, and to help fund community gardens and other seed saving projects and seed banks. Roughwood sells apothecary goods and hand-packed, hand-processed and hand-labeled seeds and offers a seed CSA, as well. In the spring of 2020, during early COVID, Smith says they saw a 100% increase in seed sales over 2019, and that so far in 2021, it’s been a 300% increase.

“It’s been astounding, it’s been wonderful! The heirloom seed movement really hit a huge resurgence, and people want to know more about where their food comes from,” Smith says.

Some upcoming Roughwood plans — all still in the works with dates TBD — include a lecture on three-sisters gardening (the practice of growing corn, beans and squash together), a fundraiser at Elwood, and promotional lectures for Dr. Weaver’s forthcoming book, “The Roughwood Book of Vegetable Cookery.” For more info on all of this, head to the Roughwood Table’s website and follow along on Facebook and Instagram.

- All photos: Courtesy of Stephen Smith & Roughwood Seed Collection

3 Comments