Fermentation is one of humans’ oldest methods for preserving and transforming foods into more digestible (and more delicious) forms. In winemaking, this process is like a handshake with yeasts and bacteria: We will provide you with sugars, nutrients and a nice place to live, and in return you’ll help us create alcohol.

Winemakers, and other professionals who use fermentation, must guide the fermentation process with a combination of science, tradition and art, so that in the end, there is something beautiful: a liquid that captures the essence of a slice of land and the fruit it bore that can be shared and enjoyed for years to come.

It’s easy to wax poetic about wine fermentation because there is inherently something magical about it, these colonies of tiny beings that irreversibly change the chemistry of raw ingredients. But, how does it actually work? Specifically in the winemaking process, there are a lot of steps and decisions (and sanitizing! So much sanitizing) that must be accomplished to achieve a successful result.

We called in an expert to explain the ins and outs of fermentation work in winemaking. Scott Neeley is the owner and head winemaker at KingView Mead, Wine and Cider and Penn Shore Winery & Vineyards, and the current President of the Pennsylvania Wine Association. He’s been making mead and wine for nearly 15 years, and knows his way around the fermentation process.

Wine Fermentation Basics

The general timeline of wine fermentation goes like this:

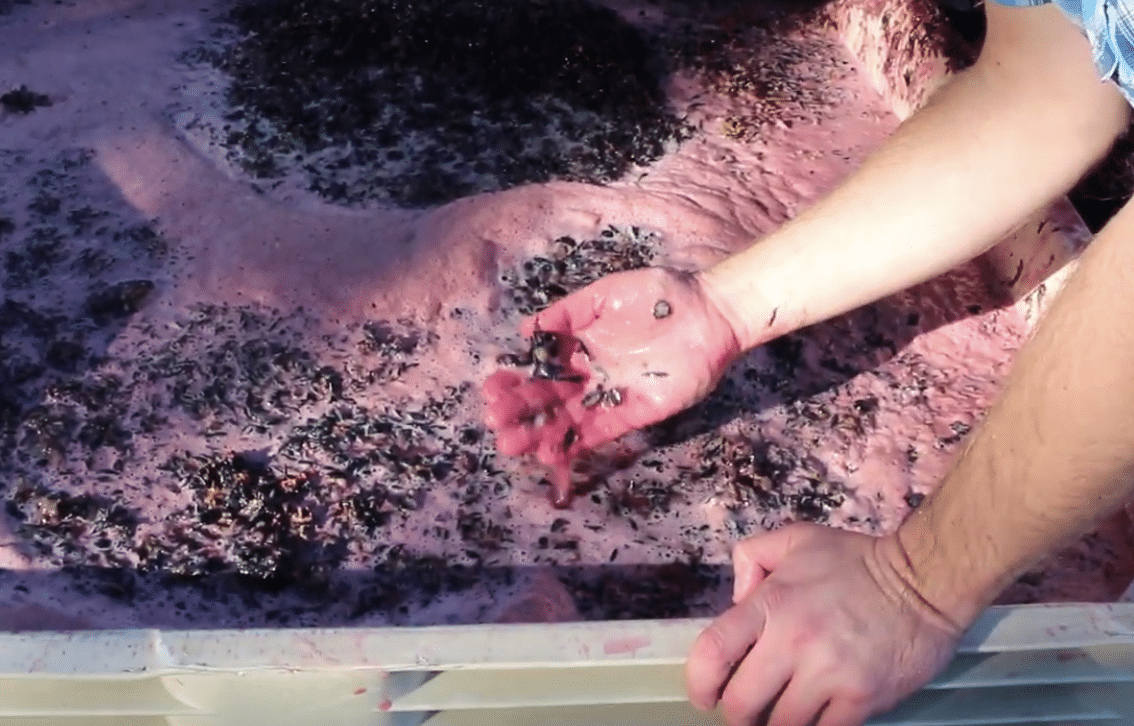

- The grapes are harvested and crushed/pressed.

- Yeast is added, or “pitched” to the juice to kick off primary fermentation. If a winemaker is doing wild fermentation, that process begins on its own.

- The wine ferments, usually in a stainless steel tank, until it’s dry.

- It may undergo a second fermentation or malolactic fermentation if the winemaker wishes.

- The wine is sometimes “back sweetened” according to the winemaker’s intentions.

- The wine is aged in barrels, or bottled.

“At the simplest level, you have a sugar concentration liquid, whether that’s juice from grapes, apples or fruits,” he says. “We call that liquid the ‘must,’ and it has the sugar that the yeast likes to consume. Once the yeasts consume it, they produce alcohol and carbon dioxide.”

The amount of sugar present in the fruit is measured in a unit called Brix. Winemakers who have close relationships with farmers and vineyard managers can monitor the Brix levels of grapes ripening on the vine and pH levels. When the Brix and pH readings are where they want them, it’s time to harvest!

Neeley works with vineyards primarily in the Lake Erie AVA (American Viticultural Area) in the northwestern corner of Pennsylvania. Here, harvest typically starts in September, and during that time, he’ll visit the vineyards on a weekly basis to measure the Brix and pH of the grapes. He’ll sample grapes from different parts and sides of the vineyards, then crush them and take the measurements. He also relies on the expertise of the farmers, who are familiar with both the “normal” weather patterns of the seasons in the region, as well as the less predictable weather events, like hail and frost, that can occur.

Deciding when to harvest or pick the grapes depends on the peak ripeness of the varietal based on the style of wine being produced. That’s part of the art of winemaking! Once grapes are harvested, the process of fermentation then begins.

Yeast

To kick off fermentation, winemakers start with a must, usually in a stainless steel fermentation tank, but sometimes in a wooden barrel. If they’re using commercial, cultured yeast, as Neeley does, they “pitch” the yeast into the must. If the winemaker is relying on wild fermentation, using only the existing yeasts on the fruit and from the air, this process will begin on its own.

“Wild fermentation is difficult because it’s relatively unpredictable … it’s kind of a gamble,” Neeley notes.

There are a handful of companies that winemakers can purchase packaged yeast from. Some strains are specific to one varietal, but mostly there are a range of grape varietals that certain yeasts are typically used for.

“Part of the science, fun and art of fermentation is playing around with different yeasts to see what works best for what you’re trying to produce,” Neeley explains. “The possibilities are almost infinite! If you take just one kind of grape, there are hundreds or even thousands of yeasts you can use, and they’re all going to have different nuances.”

Because there are natural yeasts on literally every surface around us, rigorous and constant sanitization is crucial for a successful fermentation. Other yeasts, microbes and bacteria that might sneak into the fermentation through contact with tools, equipment or handling can produce off or unwanted flavors within the wine.

Temperature

Temperature also plays a hugely important role in fermentation. There’s a reason that in many parts of the world, wine cellars are in caves, and, in some ancient winemaking regions, like Greece and the Republic of Georgia, fermentation vessels were traditionally large clay jars buried underground. A constant, predictable temperature is crucial for healthy fermentation.

“Typically, the higher the temperature, the faster something ferments, but the faster it ferments the more likely you are to lose the character of what’s being used,” Neeley says.

Many commercial wineries use something called a glycol jacket, which wraps around the fermentation tank, or is built into the tank. This thin sheath is filled with a mixture of glycol and water that regulates the temperature of the tank. There are also ways to design a fermentation room that can reduce temperature fluctuations. A concrete floor, for instance, can help moderate and conduct the room’s temperature.

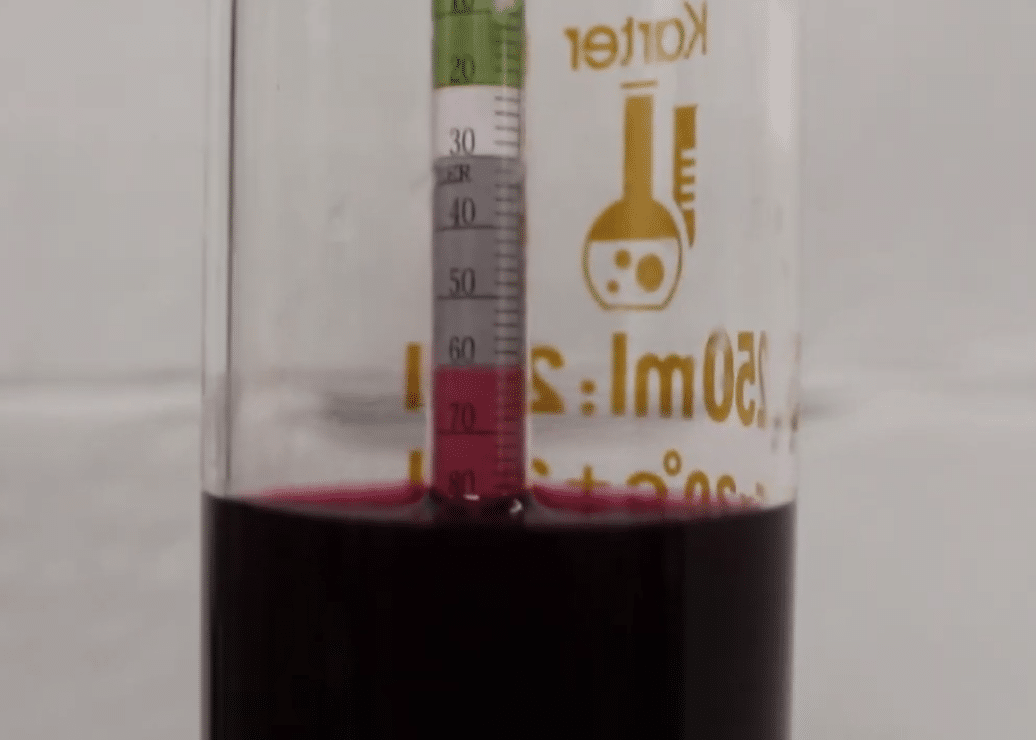

Once the yeast starts interacting with the sugars in the must, that is the start of primary fermentation. With some wines, this can take up to a few months if fermented slowly or as little as a week. Meads typically take about a month to fully ferment, and cider can ferment in just a couple weeks. A lot of winemakers use tools, like an airlock and a hydrometer to measure the progress of the process, as well as alcohol fermentation.

An airlock plugs the top of the tank, and allows carbon dioxide to be released. It’s usually filled with water or a sanitizing solution, and while the fermentation is active, the liquid in the airlock will bubble. When the bubbling diminishes, that’s a sign that fermentation is winding down, or perhaps, is stuck (more on that in a second).

A hydrometer

A hydrometer is a slender glass tube that measures how much of the sugar has been converted into alcohol; the technical term for this is “specific gravity.” Because alcohol weighs less than water, the hydrometer is placed in a sample of must, and the measurement of specific gravity is based on its buoyancy in the liquid.

Sometimes, the fermentation slows down or gets stuck because the yeast begin to die, either from lack of nutrients, an alcohol content that’s too high or a temperature that’s too hot or cold. Depending on the case, a winemaker can add nutrients and yeast to kick the process back into action.

Most wines are fermented out, meaning that the yeasts consume all of the available sugar to create a dry wine. From there, a winemaker may “backsweeten,” which means add sugar or unfermented juice to change the flavor profile. To make fruit wine, winemakers add additional fruit, like berries or stone fruit, after primary fermentation and this can spark a secondary alcohol fermentation.

Winemakers may put reds or whites through a secondary fermentation as well, which is the conversion of malic acid to lactic acid. This is commonly referred to as “malolactic fermentation” or “MLF”. This process begins by adding an enzyme that will assist in softening overly acidic or overly tannic wines. From there, a winemaker may bottle or further age the wine in barrels, tanks or bottles before releasing it for sale.

Bottled cider and wine from KingView

There is a lot more to fermentation in winemaking — people study this in university courses and spend their whole careers learning the deeper nuances of the process. But we hope it has been informative to learn the basics and understand how much science, labor and creativity goes into the Pennsylvania wines that we love to drink.

The PA Vines & Wines series was created in collaboration with the Pennsylvania Wine Association with Round 8, Act 39 grant funding from the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board (PLCB).

The Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA) is a trade association that markets and advocates for the limited licensed wineries in Pennsylvania.

- Feature photo and tank with ladder photo : Pexels

- Fermentation tanks and KingView bottles photos: KingView Mead, Wine and Cider

- Grape must photo: Deerfoot Vineyards & Winery